The “Handbook”

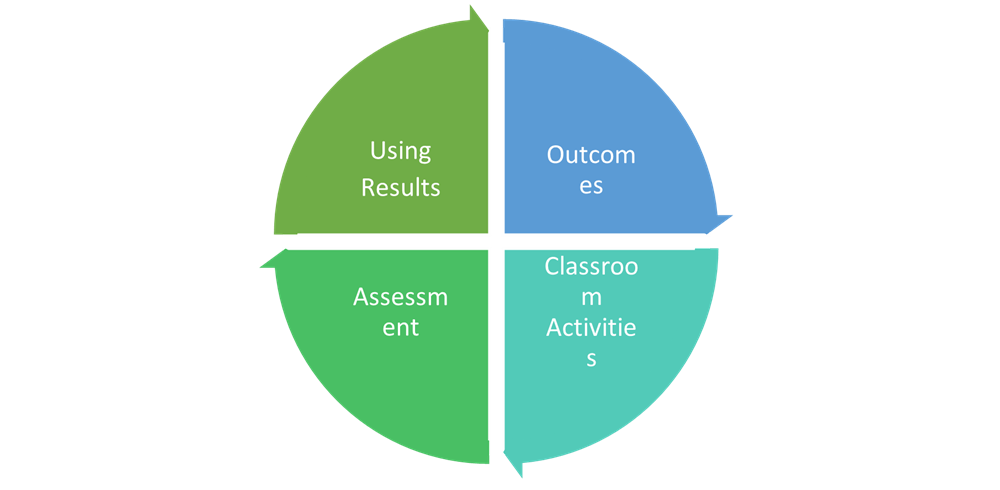

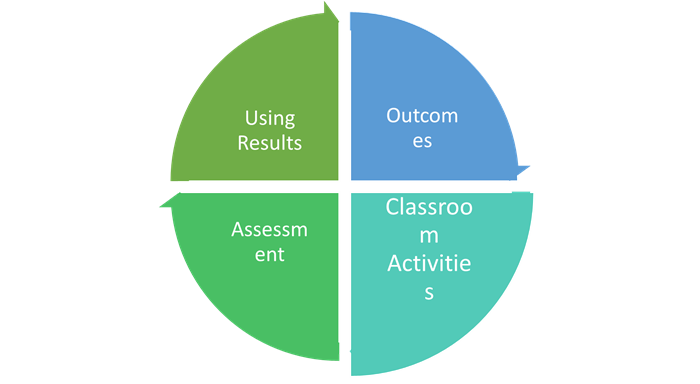

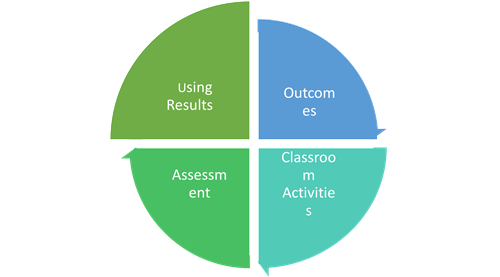

This is not your typical section of the Academic Management Section! It is intended to be a resource for developing quality learning outcomes, mapping those outcomes to each other and to classroom learning and assessment, finding better ways to use assessment results to demonstrate and improve learning, and finally, supporting faculty development. It is presented as a handbook organized around four related topics (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The Continuous Cycle of Teaching, Learning, and Assessment

Each section includes a single page with “need to know” information, a self-assessment, and content with applicable samples and resources. The final pages (appendices) include several templates to assist faculty in developing, mapping, assessing, and helping student achieve learning outcomes. As you move forward, review your program and course outcomes, revising when necessary. Then teach, assess, review, and use the results to repeat!

Let me know how I can help!

Dr. Karen Pain

Director, Assessment and Special Projects

paink@palmbeachstate.edu

Introduction: The Teaching, Learning, and Assessment Cycle: Building a Common Understanding

Think of a class you teach. What can students do that will help them in another class, on the job, or in life, as a result of successfully completing your class? You have just named a “learning outcome.” In order to achieve a learning outcome, students must master specific skills. When in your course do you ensure students can master the skills associated with the outcome you named? You have just “mapped” your outcome to the curriculum.

A few more questions. In your class, how do you communicate intended learning outcomes to students? What do you ask students to do to prove to you that they have achieved a given outcome? This is “assessment.” We often overlook the need to explicitly tell students what we expect them to learn and how we expect them to demonstrate they have learned it, yet this is a critical part of teaching and learning.

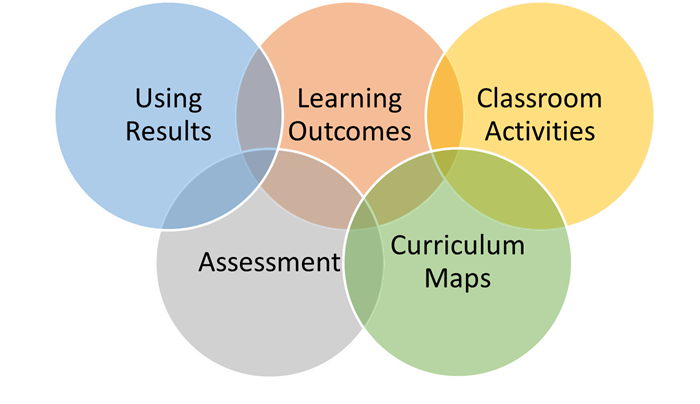

Learning outcomes, assessment, and curriculum maps are critical components of teaching and learning. It is equally important to ensure that teaching methods and classroom activities provide opportunities for students to achieve and demonstrate the learning outcomes. Finally, if we regularly use the assessment results to improve each component of our class, then we can ensure the highest quality of student learning and institutional effectiveness. These components are critical and integrated throughout any given cycle (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Critical Components of Learning

“Assessment, pedagogy, and curriculum are not mutually exclusive. In fact, they should work hand in hand, yet most institutions have yet to intentionally connect them effectively. For these reasons… higher education should strive for a culture of learning rather than a culture of assessment” (p.4).

Fulcher, Good, Coleman, & Smith (2014) |

Another question. What do you do when you realize students are not learning what you want them to learn? If you described a process to determine what might be done to help them learn better, you have described how you use results to develop improvement strategies. This is also an important part of the learning outcomes conversation. Outcomes, mapping, assessment, using assessment results, and teaching must all be used in concert to improve student learning. Fulcher, Good, Coleman, and Smith (2014)10 say it like this: “Assessment, pedagogy, and curriculum are not mutually exclusive. In fact, they should work hand in hand, yet most institutions have yet to intentionally connect them effectively.” They add, “higher education should strive for a culture of learning rather than a culture of assessment” (p.4).

Resources such as this handbook, meetings with peer faculty, and assessment workshops are part of the College’s intentional effort to merge assessment with instruction and curriculum. Such an effort is a move away from assessment for assessment’s sake and a move toward instruments and processes that inform instruction and become meaningful to all involved. In other words, these resources and opportunities are an intentional step to connect assessment, instruction, and curriculum that leads to an institutional learning culture. Many faculty members have already begun the effort to improve assessment, striving to create such a culture of learning at Palm Beach State College. Please use this handbook to join that effort.

10Fulcher, K. H., Good, M. R., Coleman, C. M., & Smith, K. L. (2014, December). A simple model for learning improvement: Weigh pig, feed pig, weigh pig. (Occasional Paper No. 23). Urbana, IL: University of Illinois and Indiana University, National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment.

Part 1: Learning Outcomes

The Need to Know Information

Main Function

Learning outcomes should exist to communicate what a student is expected to know or do after successfully completing an activity, course, program, degree, or other academic credential.

Key Points to Know

- Outcomes should focus on the major learning that shows what students should be able to do or remember a few years after successfully completing an academic experience.

- Outcomes should communicate these learning expectations to students, faculty, and the public.

- Outcomes should describe actions that student can achieve in a way that faculty can measure.

Benefits

Good learning outcomes

- provide clear instructional goals for faculty members, helping them focus curriculum on content and concepts that are most important;

- present clear expectations for the students; and

- position institutions to be accountable for student learning and learning improvement.

Learning Outcomes Self-Assessment

Take the self-assessment below related to learning outcomes in general, at Palm Beach State College, and in one or more courses that you teach. Answers are discussed throughout Part 1.

(1) If you had to pick only five things students would know or could do as a result of completing your course successfully, what would make the this “top five” list?

1.

2.

3.

4.

5. |

| (2) List your current course learning outcomes (CLOs). How well do those outcomes capture the critical learning expectations you listed in Question #1? If the current CLOs do not capture what you believe is important in the course, are you aware of the required process to revise the CLOs? |

| (3) Do your current CLOs measure higher-level thinking skills? Do you believe these levels are an appropriate expectation for this course? Why or why not? |

| (4) A health course has the following CLO: “Students will learn the respiratory system.” How could this be rewritten to show clearer expectations of the students? |

| (5) What are the institutional learning outcomes at Palm Beach State College, and how do they support general education? |

| (6) In what ways are institutional learning outcomes different from course learning outcomes? In what ways are they the same? |

| (7) What differences exist between declared, taught, and learned curriculum, and how do learning outcomes help resolve these differences? |

Defining Learning Outcomes

Terms such as goals, objectives, competencies, and proficiencies, are too often used interchangeably with the term outcomes. These terms do not always have the same meaning. Specifically, the term ‘outcome’ focuses on what the student will do while the term objective traditionally indicates what an instructor will do. So, we begin by defining learning outcomes. In short, well-written learning outcomes are statements that clearly articulate what students are expected to be able to do after they successfully complete an activity, course, program, or degree.

| Well-written learning outcomes are statements that clearly articulate what students are expected to be able to do after they successfully complete an activity, course, program, or degree. |

At the institution or program level, learning outcomes are usually expressed broadly or in general terms. General education learning outcomes and program learning outcomes are examples of broad learning outcomes. Learning outcomes at the course level are more specific. In all cases, learning outcomes communicate value to students and the public, and these expectations for student performance provide a framework that allows faculty to build the curriculum.

Why Learning Outcomes are Necessary

An assessment model grounded in learning outcomes also supports the College’s mission to provide “student-centered teaching and learning experiences.” Learning outcomes keep the College focused on student learning and allow the College to remain in compliance with its regional accreditor, the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges (SACSCOC). This handbook includes information related to the focus on student learning.

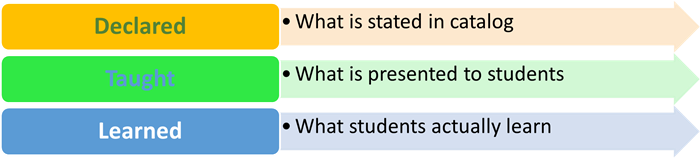

Core Questions

Learning outcomes and their assessment answer two important questions: (1) What do we want students to learn? and (2) How do we know they have learned it? These questions are relevant at the institutional, program, and course levels. The answers may seem obvious to some, but the answers are not always apparent within the curriculum. Consider, for example, what might be referred to as the three types of curriculum11: what is stated in the catalog, what instructors present to students, and finally, what students actually learn (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Three Types of Curriculum

The declared, taught, and learned curriculum types should, in theory, be the same, but without outcomes and assessment, there is no way to know if they are the same or not. Well-written outcomes help align the curriculum we declare and teach, and well-written outcomes provide the foundation for both the expectations of student learning and good assessment. Outcomes and assessment with a focus on student learning help instructors and an institution demonstrate that learning has occurred in a measurable way. This is a documented best practice that informs good teaching12. The process informs good teaching! This should be the most compelling reason to include learning outcomes and their assessment in the Palm Beach State College curriculum.

| The process informs good teaching! This should be the most compelling reason to include learning outcomes and their assessment in our curriculum. |

11Pridezux, D. (February 2003). Curriculum design. British Medical Journal, 326. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.326.7383.268

12Angelo, T.A. & Cross, K.P. (1993). Classroom assessment techniques: A handbook for college teachers. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; Maki, P.L. (2004). Assessing for learning: Building a sustainable commitment across the institution. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing, LLC.; Suskie, L.A. (2009). Assessing student learning: A common sense guide. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass

Learning Outcomes at Palm Beach State College

It is important that faculty know Palm Beach State College has learning outcomes at three levels: institutional learning outcomes, program learning outcomes, and course learning outcomes. Outcomes are developed by faculty and are published online. Web links are provided with the brief descriptions that follow.

Institutional Learning Outcomes

The current institutional learning outcomes (ILOs)13 were developed through a process of review and revision that began in 2017-2018, culminating with five ILOs (below) that became effective in Fall 2019. Each ILO is measured by a rubric developed by faculty and adapted from the AAC&U VALUE rubrics.14 The ILOs represent a broad scope of learning expected within the Associate in Arts degree, and the competencies described in the ILO rubrics map to the major areas of general education (Appendix I). Many ILOs are supported by other credit degree and PSAV programs.

- Communication: Effectively articulate in written, oral, and nonverbal formats while responding to the needs of various audiences.

- Critical Thinking: Apply evaluative, creative, and reflective thinking to form justifiable conclusions.

- Information Literacy: Ethically and effectively locate, evaluate, and use information to create and share knowledge.

- Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics (S.T.E.M.): Employ a variety of quantitative or scientific methods or technology to analyze and apply information, design and evaluate processes, draw conclusions, and propose solutions related to S.T.E.M. content.

- Socio-Cultural Understanding: Explore diverse socio-cultural perspectives, their influence on society and history, and demonstrate an understanding of social responsibility.

13Find ILOs and rubrics at www.pbsc.edu/ire/CollegeEffectiveness/ilos-2018/default.aspx

14AAC&U is the Association of American Colleges and Universities; VALUE stands for Valid Assessment of Learning in Undergraduate Education (https://www.aacu.org/value/rubrics)

Program Learning Outcomes (PLOs)

Developing learning outcomes from the existing objectives in the state curriculum frameworks at the program level (A.S., ATD, CCC, ATC, and CCP) was a major focus in the 2006-07 academic year. Outcomes-based learning continues to be an ongoing practice that now includes bachelor’s degree programs also. Outcomes at this level are reviewed annually during program review, and faculty go through a curriculum process when there is a need to revise PLOs.15

15View PLOs at www.pbsc.edu/ire/CollegeEffectiveness/ProgramLearningOutcomes/default.aspx

Course Learning Outcomes (CLOs)

Course objectives were transformed into CLOs in 2007-2008. Having measurable and meaningful CLOs is an ongoing process that is gaining momentum. Every spring since 2014, faculty have been encouraged to review their outcomes, specifically looking to ensure adequate representation of what is expected of students in each course. Faculty must go through a curriculum process to revise learning outcomes, and revisions must be approved by the cluster and curriculum committee. The College’s assessment director is available to assist faculty with outcomes development when needed. Course learning outcomes are included in course syllabi and in course outlines.16

16Search course outlines for any course at www.pbsc.edu/utilities/CourseOutlines/

Benefits of a Curriculum Driven by Learning Outcomes

Learning outcomes provide an opportunity for faculty to evaluate course and program offerings in terms of student learning. Faculty can make a difference in the learning experiences of students at Palm Beach State by collaborating with each other to define clear expectations for learning that can then be communicated to students. The implementation of learning outcomes has been and continues to be a transformative experience of how we examine students and learning as the focus has turned to what students learn and how we can improve student learning. The process is also evolutionary, and we are constantly learning. The key is that a partnership in learning develops – students know what they will be able to do as the result of the learning, and faculty will have the tools to ensure that students are learning the stated outcomes. By focusing on learning outcomes, this partnership has other benefits for both the faculty and students.

| The key is that a partnership in learning develops – students know what they will be able to do as the result of the learning, and faculty will have the tools to ensure that students are learning the stated outcomes. |

Outcomes-based Curriculum Allows Faculty to…

- Know exactly what students are expected to learn in each course and know the recommend outcomes for programs and courses.

- Provide focus for developing appropriate learning experiences for students so that they have the knowledge, skills, and abilities to succeed.

- Empower students to become more involved with their learning experiences.

- Assess students’ learning and use results as a tool for improvement.

- Grow professionally as they step away from traditional teaching formats and try innovative pedagogies to get students more involved in the learning process.

Outcomes-based Curriculum Allow Students to…

- Know exactly what is expected of them.

- Become more involved in their learning experiences.

- Apply knowledge, skills, and abilities from one class to the next or to the workplace.

Developing Learning Outcomes

There are many issues to consider when developing outcomes for any curriculum. To borrow a concept from Stephen Covey, it is important to begin this process with the end in mind.17

Begin by asking, “What will the students be able to do upon successful completion (of the degree, the program, or the course)?” Consider in the answer the knowledge, skills, and abilities you might expect a student to have years after successfully completing your course or program. There may be several outcomes, and there is no magic number of outcomes for an institution, a program, or a course. What is important is that the essential components of learning are represented. Once a desired outcome is identified, it must be developed and written.

Author Ruth Stiehl (2017)18 provides an excellent four-part backward-design model for developing learning outcomes. Her model requires faculty to collaboratively consider and find consensus regarding the concepts and issues that students must understand and address, the skills students must master, the assessments that students must take to demonstrate mastery in class, and finally, what students can do after they finish the course or program. The result of this process is an outcome for the course, program, or institution (see Table 1).

Table 1. Ruth Stiehl Model for Writing Learning Outcomes (See Appendix J for template)

| Concepts & Issues |

Skills |

Assessment Tasks |

Intended Outcomes |

| What must the learners understand or resolve to demonstrate the intended outcome? |

What skills must the learners master to demonstrate the intended outcome? |

What will learners do “in here” to demonstrate evidence of the outcome? |

What do learners need to be able to do “out there” in the rest of life? |

Once the intended outcome is identified, it must be carefully written. Good outcomes clarify expectations of the faculty member to the student and ultimately the public, so ensuring the outcome is in fact “good” becomes important.

Several qualities characterize a good learning outcome, including these.

- Good learning outcomes include action verbs.

- Good learning outcomes clearly state who is to do the action.

- Good learning outcomes clearly state what action is to be done.

- Good learning outcomes are achievable.

- Good learning outcomes are observable.

- Good learning outcomes are measurable.

- Good learning outcomes are aligned to the curriculum.

Selecting Verbs for the Outcome

Verbs to avoid

When writing learning outcomes, stay away from verbs or phrases that are not easily observed or measured. Verbs such as understand, appreciate, comprehend, and learn, are very difficult to measure or observe. When faculty lean toward using one of these words, Stiehl and Sours (2017)19 suggest a way out. Begin with the phrase, “Use their understanding of _________ to…” They provide as an example an outcome for a geriatric program: “(Use their understanding of the aging process to) observe and respond to subtle living patterns and behaviors,” and they add that one can drop the first part to begin the outcome with the action verbs. The outcome immediately becomes observable and measurable: “Observe and respond to subtle living patterns and behaviors” (Stiehl & Sours, 2017. p 49).

Tempted to write, “Students will understand?” Stop! Instead, follow the advice of Stiehl and Sours (2017).

Begin with the phrase, “Use their understanding of _________ to…” They provide as an example an outcome for a geriatric program: “(Use their understanding of the aging process to) observe and respond to subtle living patterns and behaviors,” and they add that one can drop the first part to begin the outcome with the action verbs. The outcome immediately becomes observable and measurable: “Observe and respond to subtle living patterns and behaviors” (p 49).

|

Verbs to use

Use verbs that represent observable and measurable behaviors. These are verbs such as apply, demonstrate, describe, compute, explain, analyze, evaluate, compare, conclude, defend, and construct. Many educational institutions use Bloom’s taxonomy (1956) or some variation, such as Anderson and Krathwohl (2001), as a resource because it enables faculty to rely on precise language for expressing the learning outcomes of programs and courses.

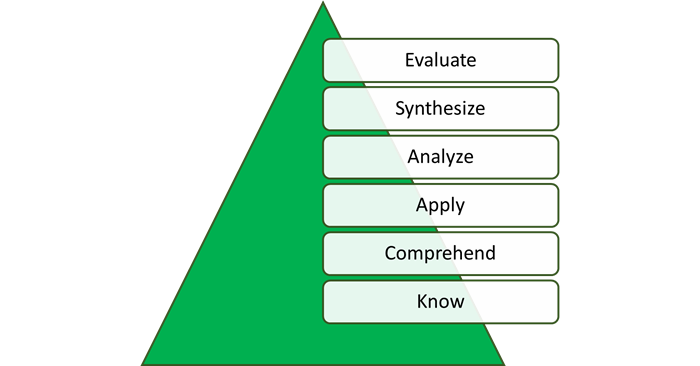

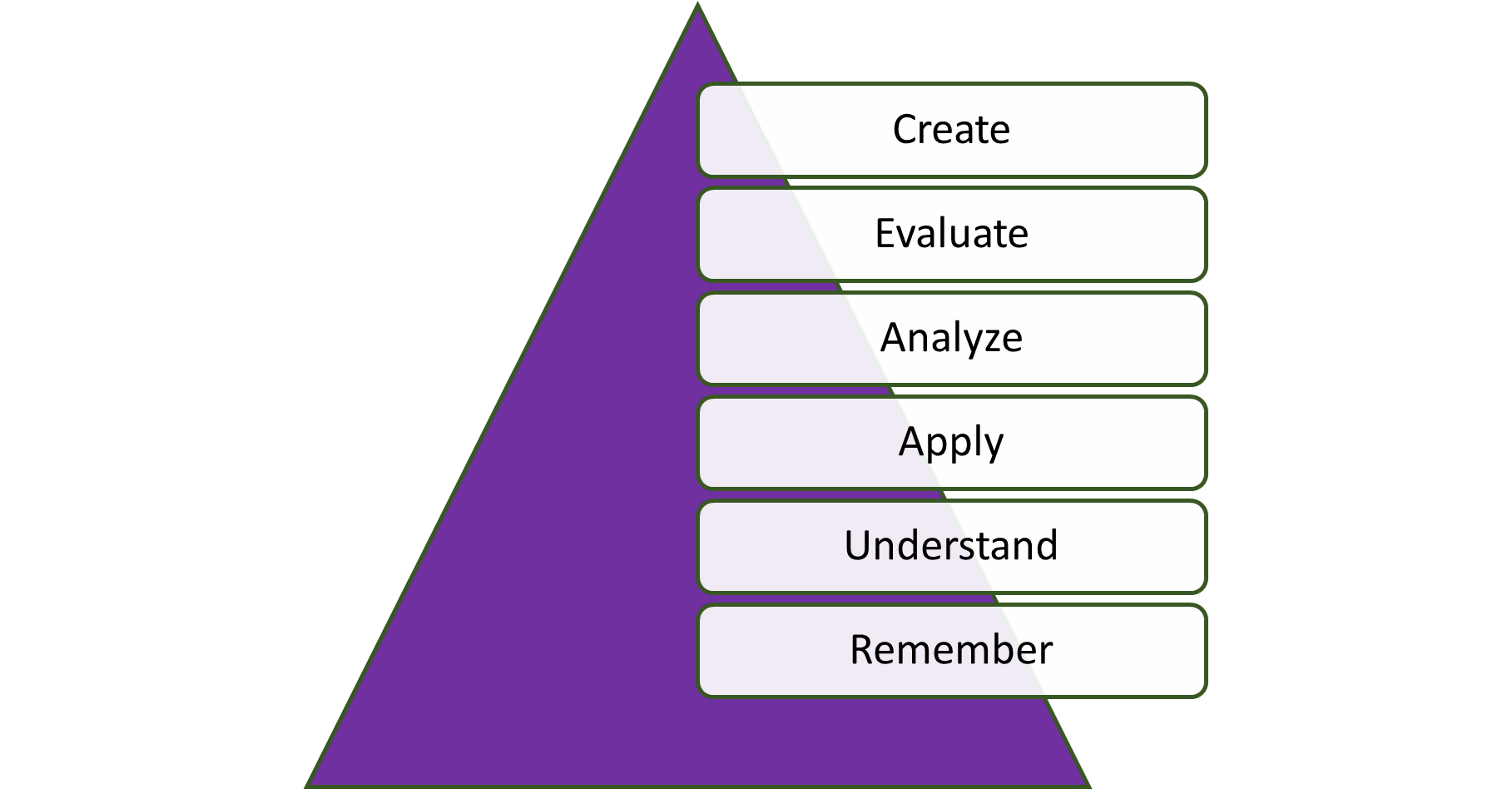

The six categories of Bloom’s taxonomy allow a faculty member to assess a different type of skill or behavior in the course, starting from the lowest level of learning, the knowledge level, to the highest level, evaluation. The taxonomy is often presented visually as a pyramid (Figures 4, 5). In this representation, the most basic methods of cognition occur at the lowest levels; learning outcomes at the college level should focus on higher levels as often as possible.

Figure 4: Bloom’s Taxonomy Pyramid - Original

Figure 5. Bloom’s Taxonomy Pyramid – Revised

While many faculty are familiar with the levels in Bloom’s taxonomy, it is usually helpful to examine the variety of verbs that may be used to construct outcomes, assignments, and assessments when the goal is to articulate the type of behaviors that are desired. Three resource tables follow to provide examples of verbs that may be selected.

Table 2 (original Bloom’s) and Table 3 (revised version) define what is meant at each level of the taxonomy, and it provides related behaviors as verbs that can be selected when developing outcomes and related activities.

Table 2. Bloom’s Taxonomy: Definition and Related Behaviors

| Category |

Definition |

Related Behaviors |

| Knowledge |

Recalling or remembering something without necessarily understanding, using, or changing it |

define, describe, identify, label, list, match, memorize, point to, recall, select, state |

| Comprehension |

Understanding something that has been communicated without necessarily relating it to anything else |

alter, account for, annotate, calculate, change, convert, group, explain, generalize, give examples, infer, interpret, paraphrase, predict, review, summarize, translate |

| Application |

Using a general concept to solve problems in a specific situation, using learned material in new and concrete situations |

apply, adopt, collect, construct, demonstrate, discover, illustrate, interview, make use of, manipulate, relate, show, solve, use |

| Analysis |

Breaking something down into its parts; may focus on identification of parts or analysis of relationships between parts, or recognition of organizational principles |

analyze, compare, contrast, diagram, differentiate, dissect, distinguish, identify, illustrate, infer, outline, point out, select, separate, sort, subdivide |

| Synthesis |

Relating something new by putting parts of different ideas together to make a whole |

blend, build, change, combine, compile, compose, conceive, create, design, formulate, generate, hypothesize, plan, predict, produce, reorder, revise, tell, write |

| Evaluation |

Judging the value of material or methods as they might be applied in a specific situation, judging with the use of definite criteria |

accept, appraise, assess, arbitrate, award, choose, conclude, criticize, defend, evaluate, grade, judge, prioritize, recommend, referee, reject, select, support |

Table 3. Bloom’s (Revised20) Taxonomy: Definition and Related Behaviors

| Category |

Definition |

Related Behaviors |

| Remember |

Recalling something without necessarily understanding, using, or changing it |

define, describe, identify, label, list, match, memorize, point to, recall, select, state |

| Understand |

Understanding something that has been communicated without necessarily relating it to anything else |

alter, account for, annotate, calculate, change, convert, group, explain, generalize, give examples, infer, interpret, paraphrase, predict, review, summarize, translate |

| Application |

Using a general concept to solve problems in a specific situation, using learned material in new and concrete situations |

apply, adopt, collect, construct, demonstrate, discover, illustrate, interview, make use of, manipulate, relate, show, solve, use |

| Analysis |

Breaking something down into its parts; may focus on identification of parts or analysis of relationships between parts, or recognition of organizational principles |

analyze, compare, contrast, diagram, differentiate, dissect, distinguish, identify, illustrate, infer, outline, point out, select, separate, sort, subdivide |

| Evaluation |

Judging the value of material or methods as they might be applied in a specific situation, judging with the use of definite criteria |

accept, appraise, assess, arbitrate, award, choose, conclude, criticize, defend, evaluate, grade, judge, prioritize, recommend, referee, reject, select, support |

| Creating |

Putting pieces of information together in a new way; reorganizing parts into a different form |

blend, build, change, combine, compile, compose, conceive, design, formulate, generate, hypothesize, plan, predict, produce, reorder, revise, tell, write |

When reviewing options for verb use, the same verb may be used in more than one level. This is true because the outcome or activity to learn the associated skills influences how the verb is applied. Tables 4 and 5 (original and revised taxonomy) provide several verbs to help construct outcomes (or assignments, assessments, or learning activities) at each level of the taxonomy.

Table 4. Suggested Verbs for Each Level of Bloom’s Taxonomy

| Knowledge |

Comprehension |

Application |

Analysis |

Synthesis |

Evaluation |

| Change |

Account for |

Apply |

Analyze |

Arrange |

Appraise |

| Choose |

Change |

Assess |

Appraise |

Assemble |

Assess |

| Define |

Cite examples of |

Change |

Calculate |

Collect |

Choose |

| Identify |

Demonstrate use of |

Compute |

Categorize |

Compose |

Compare |

| Label |

Describe |

Demonstrate |

Compare |

Construct |

Confirm |

| List |

Determine |

Dramatize |

Conclude |

Create |

Consider |

| Match |

Differentiate between |

Employ |

Contrast |

Design |

Critique |

| Name |

Discriminate |

Generalize |

Correlate |

Develop |

Estimate |

| Organize |

Discuss |

Illustrate |

Criticize |

Devise |

Evaluate |

| Outline |

Estimate |

Initiate |

Debate |

Enlarge |

Judge |

| Recall |

Explain |

Interpret |

Deduce |

Explain |

Measure |

| Recognize |

Express |

Modify |

Detect |

Formulate |

Qualify |

| Record |

Identify |

Operate |

Determine |

Manage |

Rate |

| Recount |

Interpret |

Practice |

Develop |

Modify |

Review |

| Relate |

Justify |

Predict |

Diagnose |

Organize |

Revise |

| Repeat |

Locate |

Produce |

Diagram |

Plan |

Score |

| Reproduce |

Modify |

Quantify |

Differentiate |

Predict |

Select |

| Select |

Pick |

Quantify |

Distinguish |

Prepare |

Test |

| Underline |

Practice |

Relate |

Draw conclusions |

Produce |

Validate |

|

Recognize |

Schedule |

Estimate |

Propose |

Value |

|

Report |

Shop |

Evaluate |

Reconstruct |

|

|

Respond |

Solve |

Examine |

Re-organize |

|

|

Restate |

Suggest |

Experiment |

Set-up |

|

|

Review |

Use |

Identify |

Synthesize |

|

|

Select |

Utilize |

Infer |

Systematize |

|

|

Show |

Verify |

Inspect |

|

|

|

Simulate |

|

Inventory |

|

|

|

Summarize |

|

Predict |

|

|

|

Tell |

|

Question |

|

|

|

Translate |

|

Relate |

|

|

|

Use your own words |

|

Separate |

|

|

|

|

|

Test |

|

|

Table 5. Suggested Verbs for Each Level of Bloom’s (Revised21) Taxonomy

| Remember |

Understand |

Apply |

Analyze |

Evaluate |

Create |

| Choose |

Account for |

Apply |

Analyze |

Appraise |

Arrange |

| Define |

Change |

Assess |

Appraise |

Assess |

Assemble |

| Find |

Cite examples of |

Compute |

Calculate |

Choose |

Change |

| Identify |

Demonstrate use of |

Demonstrate |

Categorize |

Compare |

Compose |

| Label |

Describe |

Dramatize |

Compare |

Confirm |

Construct |

| List |

Determine |

Employ |

Conclude |

Consider |

Create |

| Match |

Differentiate between |

Generalize |

Contrast |

Critique |

Design |

| Name |

Discriminate |

Illustrate |

Correlate |

Estimate |

Develop |

| Outline |

Discuss |

Initiate |

Criticize |

Evaluate |

Devise |

| Recall |

Estimate |

Interpret |

Debate |

Explain |

Enlarge |

| Recognize |

Explain |

Modify |

Deduce |

Judge |

Formulate |

| Record |

Express |

Operate |

Detect |

Measure |

Invent |

| Recount |

Identify |

Organize |

Determine |

Rate |

Modify |

| Relate |

Interpret |

Predict |

Diagnose |

Review |

Plan |

| Repeat |

Justify |

Produce |

Diagram |

Revise |

Predict |

| Reproduce |

Locate |

Quantify |

Differentiate |

Score |

Prepare |

| Select |

Modify |

Quantify |

Distinguish |

Select |

Produce |

| Underline |

Pick |

Relate |

Draw conclusions |

Test |

Propose |

|

Practice |

Schedule |

Estimate |

Validate |

Reconstruct |

|

Recognize |

Solve |

Examine |

Value |

Re-organize |

|

Report |

Suggest |

Experiment |

|

Set-up |

|

Respond |

Use |

Identify |

|

Synthesize |

|

Restate |

Utilize |

Infer |

|

Systematize |

|

Review |

Verify |

Inspect |

|

|

|

Select |

|

Inventory |

|

|

|

Show |

|

Predict |

|

|

|

Simulate |

|

Question |

|

|

|

Summarize |

|

Relate |

|

|

|

Tell |

|

Separate |

|

|

|

Translate |

|

Test |

|

|

|

Use your own words |

|

|

|

|

Finally, Stiehl and Sours (2017)22 recommend outcomes be written to represent what students should be able to do after leaving the current academic experience. In other words, an outcome should indicate what students will be able to do in another course, in a subsequent degree program, on a job, or even in life, after successfully completing the academic course or program. Table 6 provides ideas to promote such transferability.

Table 6. Using Verbs to Construct Outcomes that Translate Outside the Classroom

| Transferable Skill(s) |

Verbs that Lead to Evidence of the Skills |

| Creativity |

originate, imagine, begin, design, invent, initiate, state, create, pattern, elaborate, develop, devise, generate, engender |

| Psycho-motor skills |

assemble, build, construct, perform, execute, operate, manipulate, calibrate, install, troubleshoot, measure, transcribe |

| Self-appraisal or reflection on practice |

reflect, identify, recognize, evaluate, assess, criticize, judge, critique, appraise, discern, judge, consider, review, contemplate |

| Planning or management of learning |

plan, prioritize, access, use, select, explore, identify, decide, strategize, organize, delegate, order, manage, propose, design |

| Problem-solving |

identify, choose, select, recognize, implement, define, apply, assess, resolve, propose, formulate, plan, solve |

| Communication or presentation skills |

communicate, express, articulate, question, examine, argue, debate, explain, formalize, respond, rebut, justify, defend, listen, illustrate, demonstrate, organize, pace, model, summarize, inform, persuade |

| Interactive, interpersonal, or group skills |

accommodate, interact, collaborate, participate, cooperate, coordinate, structure, arbitrate, initiate, lead, direct, guide, support, decide, set goals, motivate, reflect, evaluate, recognize, enable, redirect, mediate |

In developing learning outcomes, faculty may need to consult existing course outlines as these list current outcomes. The State Course Numbering System Web page provides a search tool to find all approved and existing course numbers. Program faculty should ensure alignment to curriculum frameworks at the state level and specialized accreditors (if applicable). Links are below.

Table 7 provides sample outcomes at the institution, program, and course levels. Some examples are taken from actual outcomes at Palm Beach State College, while others are modified versions or written explicitly as an example for the table.

Table 7. Sample Outcomes (may or may not exist at PBSC)

| INSTITUTION LEVEL SAMPLES |

1. Critical thinking: Engage in purposeful reasoning to reach sound conclusions.

2. Ethics: Make informed decisions based on ethical principles and reasoning.

3. Information literacy: Find, evaluate, organize, and appropriately use information from diverse sources.

4. Communication: Employ writing, speaking, presenting, and reading skills to communicate appropriately and professionally to a variety of audiences.

5.Civility: Respectfully collaborate with diverse persons.

6. Mathematics: Use mathematical concepts to solve problems.

7. Humanities: Analyze creative arts and cultural perspectives. |

| PROGRAM LEVEL SAMPLES |

1. Accounting: Prepare basic financial statements.

2. Computer Programming: Develop application software that can access files and databases.

3. Environmental Science Technology: Explain the importance of ethics and data integrity in scientific studies.

4. Human Services: Apply knowledge of mental health and human service trends, issues, and regulations to inpatient, outpatient, and other programs within the human services delivery system.

5. Interior Design Technology: Plan interior spaces that efficiently address client needs, furniture and equipment requirements, budgets, and environmental issues.

6. Law Enforcement Officer: Demonstrate proficiency in all high liability skills (firearms, defensive tactics, vehicle operations, first aid, and dart firing stun gun).

7. Massage Therapy: Competently communicate with massage therapists, clients, patients, and health care providers.

8. Nursing: Appraise patient or client health status through analysis and synthesis of relevant data.

9. Surgical Technology: Demonstrate the skills required for surgical procedures. |

| COURSE LEVEL SAMPLES |

1. BSC 2420: Describe the major applications of modern molecular biotechnology and the implications of those applications.

2. ENC 1102: Compose non-fictional prose with a degree of formality appropriate to its subject, audience, and purpose.

3. LIT 2110: Identify significant ideas contributed to the world by international authors.

4. MAC 2233: Use integration to solve applications for business and economics.

5. MUL 1010: Analyze the stylistic characteristics of musical compositions.

6. POS 1041: Analyze national and domestic interests and foreign policy-making practices in the United States.

7. PSY 2012: Compare the theoretical principles that formed the field of psychology. |

Outcomes may also include the expected result of the action, or the result may be stated separately as a target or benchmark. Examples of a health course learning outcome are shown both ways in Table 8.

Table 8. Options for Writing Learning Outcomes*

| Outcome and target written separately |

Target integrated into outcome |

Outcome: Students will identify consumer, political, and economic issues influencing health disparities in diverse populations.

Target: At least 80% of students will score 75 points or more on the 100-point unit test that requires demonstration of the skill stated in the outcome. |

At least 80% of students will identify consumer, political, and economic issues influencing health disparities in diverse populations by scoring 75 points or more on the related 100-point unit test. |

In each case, the instructor and students in this health class know what students are expected to do after completing the related unit in the class, and they know what students must do to prove they have accomplished the outcome. Faculty also know what to look for in the assessment results to communication the degree to which students are achieving the outcome. (Assessment is covered in Part 3 of this handbook).

17Covey, S.R. (2003). The seven habits of highly effective people: Restoring the character ethic. New York: Free Press. Covey says that to “begin with the end in mind” is Habit 2.

18The New Outcome Primers Series 2.0 (2017 includes six “primers” on outcomes and related topics, published by The Learning Organization, Corvalis, Oregon. Visit www.outcomeprimer.com

19Stiehl, R. & Sours, L. (2017). The outcome primer: Envisioning learning outcomes. Corvallis, Oregon: The Learning Organization.

20Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl, D. R. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing, Abridged Edition. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

21Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl, D. R. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing, Abridged Edition. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon

22Stiehl, R. & Sours, L. (2017). The outcome primer: Envisioning learning outcomes. Corvallis, Oregon: The Learning Organization.

Assessing the Quality of Learning Outcomes

Previously, it was suggested that all outcomes be achievable, observable, measurable, and that they are aligned to the curriculum. Additionally, each outcome should include action verbs, clearly state who is to do the action, and clearly state what action is to be done.

As a final check, it is wise to assess the quality of learning outcomes. Table 9 is adapted from Stiehl and Sours23 (2017, p. 51); the original scoring template varies in rating scale and categories; it is provided in Appendix K.

Table 9 . Scoring Guide to Assess Learning Outcomes

Scores: 1 = Not true at all; 2 = Partially true; 3 = Completely true.

|

| Characteristic of Learning Outcome Statement |

1 |

2 |

3 |

Suggestions for Improvements |

| Achievable: Students can master the skills sufficiently by the end of the program or course. |

|

|

|

|

| Observable: Faculty can observe student demonstration of the outcome. |

|

|

|

|

| Measurable: Faculty can articulate the degree to which students have accomplished the outcome. |

|

|

|

|

| Aligned to the Curriculum: A curriculum map has been created and shared with all program or course faculty. |

|

|

|

|

| Verb use: Action verbs are used. |

|

|

|

|

| Verb use: It is clear what action is expected of the students. |

|

|

|

|

| Verb use: It is clear that the students are the ones expected to do the action. |

|

|

|

|

23Stiehl, R. & Sours, L. (2017).

The outcome primer: Envisioning learning outcomes. Corvallis, Oregon: The Learning Organization.

Part 2: Aligning Classroom Teaching and Learning to Outcomes

The Need to Know Information

Main Function

Every instructor should offer classroom activities that are directly aligned to learning outcomes so that students have opportunities to be introduced to related concepts and to practice or master related skills. This does not mean that all activities must be connected to a learning outcome, but it does mean there should be at least one activity aligned to every learning outcome.

Key Points to Know

- A classroom activity that is aligned to learning outcomes might be used to introduce students to content related to a given outcome, or the activity might be used to give students the opportunity to practice or master related skills.

- Students must be given opportunities to learn, practice, or master related content if there is an expectation for them to do so.

Benefits

Classroom activities that are aligned to learning outcomes

- help faculty members know where in the curriculum they will introduce related content to students or give students opportunities to practice or master related skills and abilities;

- provide opportunities for students to engage with related content, knowledge, skills, and abilities; and

- build in formative assessment opportunities which help faculty members know how well students are achieving a given outcome before it is time to formally assess.

Classroom Activities Self-Assessment

Take the self-assessment below related to classroom activities in one or more of the courses you teach. You should be able to answer each question affirmatively and in appropriate detail by the end of this section of the handbook.

| (1) Do you know when in the course schedule you introduce, reinforce, or expect mastery of the information or skills that are associated with each course learning outcome (CLO)? |

| (2) How do you give students the opportunity to practice demonstrating achievement of each CLO in your course? |

| (3) To what extent have you engaged in a mapping exercise to document what activities you present to students to give them the opportunity to practice and demonstrate achievement of each CLO in your course(s)? |

| (4) What activities do you use that require higher order thinking skills? |

Getting Started

You have good outcomes. Now what? Good outcomes mean nothing if several things do not happen. Students should know the outcomes. In fact, students should be explicitly told what the outcomes are, because it lets them know what they will be expected to demonstrate during or by the end of the course or program. Faculty should know where in the curriculum students have the opportunity to be introduced to related skills and when students can practice those skills. It should also be clear to the faculty member, students, and external evaluators what assessments allow students to demonstrate those skills.

Curriculum maps are excellent tools to articulate this information and should be considered before building classroom activities. Maps provide a “check and balance” for faculty members and the institution. Curriculum mapping is an exercise that can be done at all levels. Mapping allows faculty to document connections between program and institutional outcomes, between course and program outcomes, and between course activities, assignments, or assessments and outcomes at any level.

Mapping Learning Outcomes to the Curriculum

Begin by asking for any outcome, “In what program, course, or session will students be introduced to and master the necessary skills associated with this outcome?” How a map is created really depends on the level of outcomes being mapped, and specific terms used may vary among institutions that use curriculum mapping. Curriculum maps “front-load” a lot of work in planning a course or program, but once a curriculum map is complete, it provides clear direction for instruction and assessment.

Terminology of a Curriculum Map

Typically, a curriculum map includes three levels of activity related to outcomes. Many institutions use the terms “introduce” and “reinforce” to describe the first two levels. The highest degree may be described by what the faculty will do (emphasize, provide extra coverage) or what the students will do (master). In this section, the terms “introduced, reinforced,” and “emphasized” will be used to describe activity levels.

- Introduced – students likely see content or learn a skill for the first time.

- Reinforced – students are typically given an opportunity to practice related skills or apply related knowledge.

- Emphasized – students are typically expected to demonstrate mastery.

Curriculum Map: Descriptions and Samples

Table 10 describes curriculum maps at each level of the curriculum. Examples follow in Tables 11 through 13. Map templates are provided for program (Appendix L) and course learning outcomes (Appendix M).

Table 10. Curriculum Map Descriptions based on Outcome Levels

| Level |

Process |

Product |

| Institutional learning outcomes (ILOs) |

Faculty who teach each course determine whether students learn skills required to achieve a given ILO in the course and, as applicable, whether the skills are introduced, reinforced, or emphasized. |

Chart matches each ILO with the courses in which students will learn the skills required to achieve that ILO, indicating further whether the skills are introduced, reinforced, or emphasized for a given outcome in a given course. |

| Program learning outcomes (PLOs) |

Program faculty determine in which courses students learn skills required to achieve each PLO, and in each case, whether the skills are introduced, reinforced, or emphasized, and which, if any, ILOs are supported by each PLO. |

Chart matches each PLO to the program courses, indicating in each applicable course, whether the skills required to achieve the PLO are introduced, reinforced, or emphasized. Additionally, PLOs are matched to ILOs as applicable. |

| Course learning outcomes (CLOs) |

Faculty who teach the course determine when in the course the skills required to achieve each CLO are introduced, reinforced, or emphasized (e.g., point in time, textbook chapter, etc.), and which, if any, ILOs or PLOs are supported by each CLO. |

Chart matches each CLO to the course content, indicating when skills required to achieve each CLO are introduced, reinforced, or emphasized. Additionally, the CLOs are matched to PLOs or ILOs as applicable. |

Table 11. Sample Curriculum Map for Institutional Learning Outcomes (ILOs)

Selected Courses and Sample ILOs Only: (I = Introduced, R = Reinforced, E = Emphasized)

|

| Course |

ILO #1

Communication |

ILO #3

Civility |

ILO #2

Critical Thinking |

ILO #4

Numeracy |

ILO #5

Information Literacy |

ILO #6

Scientific Reasoning |

| AMH 2010 |

I |

R |

|

|

E |

|

| BSC 1010 |

|

|

E |

R |

I |

E |

| ENC 1101 |

E |

|

E |

|

R |

|

| FIL 2000 |

R |

|

E |

|

|

|

| MAC 2312 |

|

|

R |

E |

|

|

| SPC 1017 |

E |

E |

R |

|

R |

|

Table 12. Sample Program Map (Possibility for Paralegal ATC)

| Course |

PLO #1

Theory |

PLO #2

Communication |

PLO #3

Technology |

PLO #4

Solve Problems |

PLO #5

Legal Systems |

| PLA 1003 |

E

|

I

|

I

|

|

I

|

| PLA 1104 |

|

E

|

|

|

|

| PLA 2114 |

|

|

|

I

|

I

|

| PLA 2209 |

|

|

|

R

|

R

|

| PLA 2229 |

|

|

E

|

E

|

E

|

| ILOs Supported |

|

Communication |

|

Critical Thinking |

Critical Thinking

|

Table 13. Sample Curriculum Map for Course Learning Outcomes

(Possibility for TRA1154 Supply Chain Management)

| Unit |

CLO #1

Business Functions |

CLO #2

Problem Solving |

CLO #3

Key Processes |

CLO #4

Issues and Challenges |

CLO #5

Customer Value

Logistical Decisions |

| 1 |

I |

|

|

I |

|

| 2 |

|

|

I |

|

I |

| 3 |

|

I |

|

R |

R |

| 4 |

|

R |

|

R |

E |

| 5 |

|

|

|

E |

E |

| PLOs Supported |

Business Practices |

Problems and Solutions |

Business Knowledge |

Problems and Solutions |

Flow and Distribution |

| ILOs Supported |

|

Critical Thinking |

|

Critical Thinking |

Communication

Critical Thinking |

In each case, the curriculum map assures faculty and the College that all outcomes are covered within the curriculum and at various levels of depth. Maps also provide a foundation for developing appropriate assessment, which, ideally, is developed at the same time. Templates are provided online at www.pbsc.edu/ire/CollegeEffectiveness (see also Appendices K and L).

Building Classroom Activities that Lead to Outcomes Achievement

After mapping the curriculum, a faculty member should be well acquainted with not only each learning outcome but also the extent to which related skills and knowledge are included in the course. Faculty should know at this point if students are simply introduced to the content in the course. Faculty should know if they will reinforce previously learned content, giving students the chance to practice related skills or if the student is expected to demonstrate mastery of related skills in the course.

It is important to consider a taxonomy, such as Bloom’s, in which levels of thinking are considered as activities are built into the classroom. When connecting thinking to a curriculum map, the Baltimore County school system considers this a “Three-Story Intellect”24 and relates each “story” to both the level of thinking and of demonstration.

- Introducing knowledge and skills (knowledge and comprehension) is the “basement”.

- Practicing the use of knowledge or skills (application and analysis) is “the ground floor“.

- Demonstrating or mastering knowledge and skills (synthesis and evaluation) is “the penthouse”.

Refer back to Tables 3, 4, and 5 in the previous section for several verbs that are appropriate when creating activities and assignments in class to address the various levels of expectation.

Once a faculty member knows the level of expected learning for an outcome, there are many activities, either introduced by the instructor or completed by students, to accomplish the intended level. Linda Nilson (2010)25 provides a crosswalk of methods and the most likely level of associated learning. She suggests that lectures alone tend to present knowledge but no higher-level thinking. If some type of interaction is included, students may understand the content better, and with intentional design, they may engage in higher-level thinking. According to Nilson, activities that lead to greater learning are those which require writing or speaking, providing feedback to others, case studies, high levels of inquiry, projects, reflections, service-learning, and clinical or on-site work (p. 107).

In other words, if a curriculum map verifies that only an introduction to knowledge or skills is necessary, a lecture may suffice, and instructors can often select activities that require only lower levels of thinking. However, if knowledge and skills are to be practiced by the student, instructors should seek activities that will require students to apply and analyze content. Finally, if students must demonstrate mastery of knowledge or skills, instructors should consider classroom activities that will promote the higher-level thinking skills of synthesis and evaluation.

Table 14 provides sample ideas to align instructional methods and classroom activities to learning outcomes. Lists are not intended to be comprehensive.

Table 14. Sample Classroom Activities Aligned to Learning Outcomes

Desired Coverage or Demonstration of Achievement

|

| Introduce Related Content |

Students Practice

Related Skills |

Students Demonstrate Mastery of Outcome |

1. Lecture

2. Slide presentation

3. Provide handout(s)

4. Provide worksheet(s)

5. Group discussion

6. Chunk content

7. Relate to prior knowledge

8. Content outlines

9. Examples and graphics

10. Students to recall, identify, restate, and relate |

1. Discuss and summarize

2. Write

3. Labs

4. Self-assess

5. Review

6. Collaborate

7. Expand outlines

8. Make connections

9. Solve structured problems

10. Select strategies

11. Develop questions

12. Classify, categorize

13. Analyze

14. Brainstorm |

1. Complete a project

2. Conduct research

3. Solve complex problems

4. Perform a case study

5. Evaluate previous or peer work

6. Justify and defend

7. Create models

8. Provide thorough explanations

9. Develop examples metaphors, analogies

10. Draw inferences and conclusions

11. Explain validity of information |

24A three-story intellect: Bloom’s taxonomy and Costa’s Levels of Questioning. Retrieved from https://www.bcps.org/offices/lis/researchcourse/documents/questioning_prompts.pdf

25Nilson, L.B. (2010). Teaching at its best: A research-based resource for college instructors (3rd Ed). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass

Part 3: Assessment of Learning Outcomes

The Need to Know Information

Main Function

Assessment should inform teaching and improve student and institutional learning.

Key Points to Know

- Assessment should provide useful information to faculty and the institution.

- Assessment should measure the intended learning outcomes.

- Assessment should never be used punitively.

- Assessment is not perfect.

Benefits

- Good assessment is a tool for learning: it lets students demonstrate outcomes achievement with feedback to tell them where they are missing the mark and allows faculty adjust teaching when necessary.

- Good assessment lets faculty know what progress is being made toward an outcome.

- Good assessment lets faculty test what they teach instead of teaching to a test.

- Good assessment lets faculty stay ahead of legislation.

- Good assessments provide a way for faculty and the institution to articulate student learning to internal and external constituents.

Self-Assessment on Outcomes Assessment

Take the self-assessment below related to assessment in one or more courses you teach. Answers will vary and are discussed throughout Part 3.

| (1) What types of assessments do you currently use in your course(s)? |

| (2) Have you mapped your assessments to your course learning outcomes (CLOs) or otherwise documents how and when you measure CLO achievement? |

| (3) How do you communicate to students what type of assessment(s) they will complete and how the assessment(s) will measure their achievement of the outcome? |

| (4) How do you utilize formative assessment? |

| (5) How well do you believe your current assessments measure your CLOs? |

| (6) How often do you discuss assessment with colleagues who teach the same course(s) as you? |

Why Assessment is Necessary

Why do faculty give grades to students instead of trusting that each one learned what was taught? One might presume grades are assigned to let students know they have learned (or not). Grading then becomes a tool for learning and growing because it helps students learn what they did and did not understand in the material.

In this same way, assessment is a tool. Just as the students can use grades to improve, assessment is about getting the same benefit for ourselves. Specifically, assessment affords an opportunity to gather feedback we can use for our own benefit. The primary purpose of assessment is to improve learning (Angelo & Cross, 1993; Maki, 2004; Suskie, 2009)26. Stiehl and Null (2018)27 suggest we assess for three reasons: to assist students with learning, to advance students through a program of study, and to adjust our teaching or curriculum.

Assessment, while never perfect, is a tool to help faculty and an institution know and articulate how well students are achieving course and program learning outcomes. Prior to the learning outcomes model currently in place throughout colleges and university systems, assessment efforts were more focused on indirect measures and assessments of achievement, such as GPA and transfer rates. Although these measures are still monitored, the current model provides greater benefits for faculty and students by incorporating direct measures such as assignments and assessments that are embedded at the course level.

26Angelo, T.A. & Cross, K.P. Cross (1993). Classroom assessment techniques: A handbook for college teachers (2nd Ed). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.; Maki, P.L. (2004). Assessing for learning: Building a sustainable commitment across the institution. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing, LLC.; Suskie, L. (2009). Assessing student learning: A common sense guide (2nd Ed). ). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

27Stiehl, R. & Null, L. (2017). The assessment primer: Assessing and tracking evidence of learning outcomes. Corvalis, Oregon: The Learning Organization.

Getting Started

If you have not already, you are strongly encouraged to create a curriculum map (see Part 2 of this handbook) so you know where in the curriculum the outcomes and related content are introduced, reinforced, and emphasized. A curriculum map can also be utilized to “map” assessment to the outcomes. After you know what you expect students to do or know and when, you can select the right tools and develop an assessment plan. An outcomes assessment plan helps an instructor, program faculty and staff, and even an institution know what will be assessed, when it will be assessed, and how it will be assessed.

Developing assessment plans for an outcomes-based curriculum is far from unique to Palm Beach State College. It is good practice and commonly accepted in higher education, and many good resources are available, such as those found on websites such as the National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment, the American Associate of Colleges and Universities Assessment and VALUE, James Madison University Assessment Resources, and the University of Hawai’i Manoa.

Selecting Assessments

Assessment should be both formative (along the way) and summative (near or at the end), and multiple measures should be built into an assessment plan. Assessment should measure student performance and capture specifically the skills required to achieve a learning outcome. Assignment grades should not be used to assess a learning outcome unless the grade equates to a score that specifically measures the skills associated with achievement of the outcome.

When choosing an assessment, be certain you know why you are using it, who will assess and be assessed, what outcome it will measure, and what the scores will help you know or understand about student learning. Include direct measures, that is, assessments that require student performance directly related to a learning outcome.

Direct Measures of Learning Outcomes

Each assumes a clear relationship to a given outcome.

- Ratings of student performance

- Rubric scores on projects, presentations, research, written work, or other assignments

- Portfolios

- Quiz or test scores

- Results of student performance observations

- Results of skills-based or lab-based performance

- Results from student response systems

Indirect Measures of Learning Outcomes

- Course grades (will not give any information related to achievement of individual outcomes)

- Grades on projects, presentations, research, written work, or other assignments unless a rubric or scoring criteria clearly relate the assignment to a specific outcome

- Scores on external exams for entry into other programs unless the exam has isolated content scores that can be directly related to a specific outcome

- Satisfaction surveys

- Course evaluation surveys

Scoring Guides, Rubrics, and Checklists

Scoring guides, rubrics, and checklists can be effective assessments for formative assessment because such instruments typically include multiple criteria that students must master before taking a summative assessment to show they have achieved an outcome. Scoring guides and rubrics can be effective as summative assessment instruments. These tools most often clearly state criteria and require an instructor to either “rate” the degree to which the students meet the criteria or simply indicate the student does or does not meet each expectation. Scoring guides and rubrics can be applied to (used to score) a variety of assignments, including projects, presentations, research, written essays or papers, case studies, skill demonstrations, and more, and – assuming multiple faculty use the same scoring instrument and calibrate their use of the instrument – trend analysis becomes possible. Trend analysis allows faculty to address the degree to which their students are learning in the classroom, and trend analysis allows an institution to discuss the quality education it provides.

Selecting Performance Standards

Standards are often referred to as achievement targets, benchmarks, or expectations. Standards help faculty and the institution know the degree to which students are learning and easily provide a way to articulate student learning to each other and to external stakeholders. Setting standards and recording whether students meet those standards (or do not) is an important part of closing the assessment loop each cycle. There are multiple considerations when selecting standards.

Minimum Scores

A standard might be a minimum score, say a score of “4” on a 5-point rubric. It might also be a comparison to an external score such as a national benchmark, for example equal to or greater than the national average for students at a community college. A standard might also be set against previous performance, for example, with an expectation of annual improvement or maybe a demonstrated gain by the end of a semester over a pretest taken during the first week.

Achievement Targets

After a standard is established, it is also important to know the expected percentage of students who should meet the standard. In some cases, for example a licensure exam, meeting a standard may be a requirement to complete the program. In other cases, faculty may expect that a minimum percentage of students, say 80%, will achieve a minimum score. In still other cases, faculty may be looking for improvement over an initial point in time or an initial score.

Sample achievement targets include the following:

- 95% of students will demonstrate the skills safely and accurately in a lab setting.

- 75% of student scores will score at least 20 points higher on the post-test than on the pre-test.

- 80% of students will achieve a B or higher on the exam.

- 80% of students who take the licensure exam will achieve a score equal to or greater than the national average.

Developing Assessment Plans

Assessment plans at the institutional, program, or unit level should be developed with content experts to ensure careful alignment to the outcomes. Assessment plans should include very specific components, and the plans should be documented. Faculty developing assessment plans for a course should consider documenting the plan on a template similar to one provided in this handbook (Tables 12 and 13, Appendix M and Appendix N).

Assessing the Assessment Plan

Assessment plans should be evaluated for clarity and connection to the curriculum. The following criteria should be met when choosing assessment instruments and benchmarks.

- Selected assessments purposefully measure an intended outcome.

- Selected assessments are affirmed by content experts (faculty, staff, or literature).

- Selected assessments provide information that is as accurate and valid as possible.

- The assessment plan includes multiple measures with at least one direct authentic measure of student learning for each learning outcome.

- Achievement targets are clearly stated and justified by faculty who teach the related content.

- Data collection processes are explained and appropriate.

- The plan includes ways to share, discuss, and use the results to improve student or institutional learning (see Part 4 of this handbook).

Two options for “assessing assessment plans” are included as Appendix O and Appendix P.

Components of an Assessment Plan

Plans at all levels (institutional, program, course) should include at a minimum, the measures and achievement targets for each learning outcome. Every outcome should have at least one measure and a corresponding standard should be established for each measure. The standard may be called something else such as benchmark or achievement target. Currently at Palm Beach State, both terms are used in assessment plans.

Implementation and Data Collection

Good assessment plans also include details regarding implementation and data collection. For example, if a course-level assessment is selected as a program measure, the assessment plan should clarify for all instructors in that course what the assessment items are and exactly when in the course the assessment is to be administered. “When” may be inherent because it is stated as a specific unit or lab within the course. However, if an assessment is not specific to a unit test or assignment, it should be clear what elements of the course should be covered before students take the assessment or complete the assignment.

An assessment plan can succinctly clarify other important details. Consider including:

- Semesters or date ranges for the assessment cycle

- Who will be assessed (students in what class?)

- When in that cycle the data are to be collected (state any specific unit(s) that must be covered before the assessment is administered, or provide a time frame such as ‘during the last regular week of class’)

- Directions for reporting results

All academic programs at Palm Beach State College have developed assessment plans, and faculty in many courses have done the same. Following are sample plans for both a program (Table 15) and a course (Table 16). In each case, only a portion of the plan is provided. A template to write an assessment plan is provided as Appendix N.

Table 15. Sample Program Assessment Plan (adapted from Electrical Power Technology)

Assessment Plan for Electrical Power Technology

Cycle: May 18, 2017 through May 11, 2018

|

|

PLO # 1:

Perform inspection and maintenance of industrial measuring equipment and transmitters, final control elements, and transducers. |

PLO # 2:

Troubleshoot instruments and controls equipment and systems. |

PLO # 3:

Interpret P&D diagrams and control loops. |

Measure(s)

How will the PLO be assessed?) |

Scores on “Inspection and Maintenance” exam in ETS2530C

0=Not taken

1=Unsuccessful

2=Partially successful

3=Successful, but exceeds 60 minutes to complete

4=Successfully completes all tasks in 75 minutes

5=Successfully completes all tasks in 60 minutes. |

Scores on lab assignments 1 and 2 (“Troubleshooting”) in EET2930

0=Not completed

1=Unsuccessful

2=Partially successful

3=Successful, but exceeds 60 minutes to complete

4=Successfully completes all tasks in 75 minutes

5=Successfully completes all tasks in 60 minutes. |

Scores on lab assignments 3 and 4 (“Diagrams and Control Loops”) in EET2930

0=Not completed

1=Unsuccessful

2=Partially successful

3=Successful, but exceeds 60 minutes to complete

4=Successfully completes all tasks in 75 minutes

5=Successfully completes all tasks in 60 minutes. |

Achievement Target(s)

What is an acceptable performance level?) |

80% of students who take the “Inspection and Maintenance” exam in ETS2530C will score a 4 or 5. |

80% of students who complete the “Troubleshooting” labs in EET2930 will score a 4 or 5 on each one. Scores will be reported separately for each lab, and the outcome is achieved only if targets are met on both labs. |

80% of students who complete the “Diagrams and Control Loops” labs in EET2930 will score a 4 or 5 on each one. Scores will be reported separately for each lab, and the outcome is achieved only if targets are met on both labs. |

| Which, if any, GELO(s) or ILO(s) are supported? |

Critical Thinking |

Mathematics |

Critical Thinking |

Table 16. Sample Course Assessment Plan (Adapted from ETS2530C)

Assessment Plan for Process Control Technology (ETS 2530C)

Program: Electrical Power Technology

Cycle: May 18, 2017 through May 11, 2018

Reporting: Faculty report results for each section each semester to department chair.

|

|

CLO # 1:

Describe the Fundamentals of Process Control. |

CLO # 2:

Describe set point and error. |

CLO # 3:

Explain input and output. |

Measure(s)

(How will the PLO be assessed?) |

Free response answer to “Process Control” question on Test 1.

0=Does not take test or does not describe at all.

1=Provides related but incorrect description.

2=Provides partially correct and partially complete description.

3=Provides complete response that is mostly correct.

4=Provides complete and accurate description. |

Free response answer to “Set Point and Error” question on Test 4.

0=Does not take test or does not describe at all.

1=Provides related but incorrect description.

2=Provides partially correct and partially complete description.

3=Provides complete response that is mostly correct.

4=Provides complete and accurate description. |

Explanation during end of term project presentation

0=Does not complete project or does not include explanation of input and output at all.

1=Provides related but incorrect explanation.

2=Provides partially correct and partially complete explanation.

3=Provides complete explanation that is mostly correct.

4=Provides complete and accurate explanation. |

| Achievement Target(s) |

At least 80% of students will score a 3 or 4. |

At least 80% of students will score a 3 or 4. |

At least 80% of students will score a 3 or 4. |

| Which, if any, PLO(s) are supported? |

PLO#1: Industrial measuring equipment and transmitters, final control elements, and transducers |

|

|

| Which, if any, GELO(s) or ILO(s) are supported? |

|

Mathematics |

Critical Thinking Communication |

Authentic Assessment

The assessment plan should address the issue of the type and amount of credit students can earn for participating in the assessment. Specifically, faculty should discuss how much credit and whether credit earned is “extra” or “authentic,” meaning it is applied to the course grade. Authentic assessment is, of course, preferred. When students participate in assessment with results attached to their course grade, they are more likely to give their best effort, and faculty are more likely to find the results useful to improve learning.

In some programs, faculty will not have options regarding how to award credit, but in those cases where it is optional, ideally, faculty will try to agree on a percentage of the grade a student can earn on the assessment. For example, faculty may agree that the assessment will be worth between two and three percent of the total grade.

Part 4: Using the Results

The Need to Know Information

Main Function

Assessment results should be used to improve student or institutional learning.

Key Points to Know

- Assessment can only become meaningful if results are shared, discussed, and used to improve learning.

- Assessment results should never be used punitively.

- Results of one cycle should inform improvement strategies for the next cycle.

Benefits

When assessment results are reviewed with the intent to improve learning

- Discussion and reporting are improved: Faculty can point to tangible evidence when they report their students are (or are not) learning.

- Teaching is improved: Faculty can know how to adjust teaching when they see where students have skill deficiencies. In many cases, faculty can know how their students perform compared to other students, helping those faculty members hone their teaching methods.

- Collaboration is enhanced: Regular conversations about results can lead to discussions of best instructional methods, wider benchmarking and comparisons, common challenges and effective solutions, and more.

Self-Assessment on Using the Results

Take the self-assessment below related to using assessment results. Content is discussed throughout Part 4.

| (1) To what degree have you participated in conversations with colleagues who teach the same course to discuss assessment plans and results? |

| (2) Why is it important to use assessment results? |

| (3) What is meant by the phrase “closing the loop” as it relates to assessment? |

| (4) In your opinion, what should happen when outcomes are achieved at the college level or in the course(s) that you teach? |

| (5) In your opinion, what should happen when outcomes are not achieved at the college level or in the course(s) that you teach? |

| (6) Name at least three questions that should be asked by a faculty member who is reviewing his/her results in comparison to college-wide results. |

It is critical to understand that assessment is not meaningful unless and until the results are used appropriately. Assessment becomes meaningful only when faculty and others review the results and use those results to inform instruction and improve learning – their own or that of their students.

Review at Palm Beach State College varies based on the type of outcomes assessed.

- Institutional learning outcomes and general education competencies – review is most often by open invitation, done in small forums, campus meetings, cluster reviews, during Development Day breakout sessions, or in committee meetings. Faculty review results and develop improvement strategies to be implemented in the next cycle.

- Program learning outcomes - annual review includes a review of learning outcomes assessment results. Program faculty review the results, select at least one outcome to target for improvement unless all have been met and other data points are selected, and develop action plans for the next cycle.

- Course learning outcomes - review is conducted individually by faculty during the annual appraisal or preparation for continuing contraction portfolio. Faculty reflections on and use of assessment results are documented and shared with associate deans.

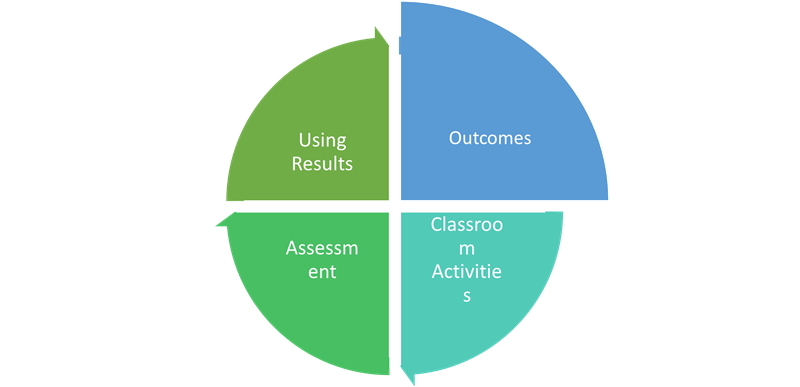

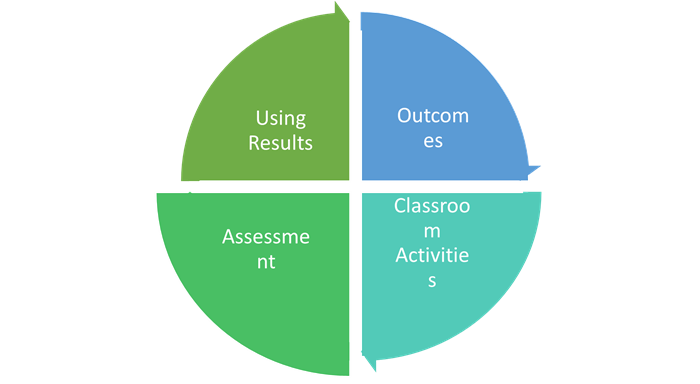

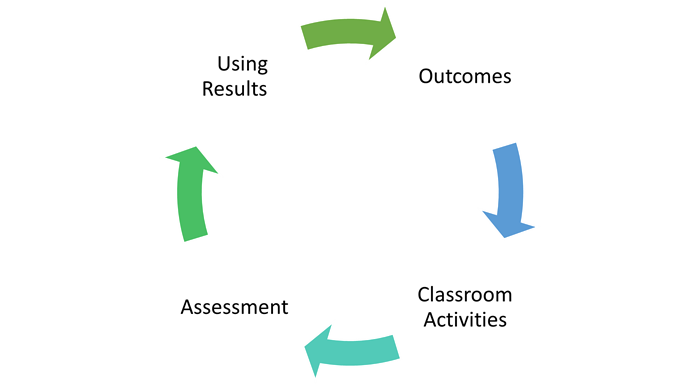

In a conversation about using the results, it is helpful to return to the cycle that has been presented in each section of this handbook, this time thinking of it as a continuous loop (Figure 5). It truly never ends!

- We must develop outcomes, the important learning goals we set for students.

- We must ensure classroom activities will provide opportunities for students to learn what we want them to learn and achieve the outcomes.

- We must assess. How else can we know whether and to what degree they know and do what we expect them to know and do?

- Finally, we must use those results to figure out what to do next, but then it starts all over, completing yet continuing the cycle! Results may lead us to keep or revise the outcomes, but we must start all over again based on the learning goals.

Figure 6. The Teaching, Learning, and Assessment Cycle

In education, reviewing assessment results and planning for the next teaching, learning, and assessment cycle is often referred to as closing the loop. When the loop is closed on each cycle, the discussion typically includes a review of several components.

- Faculty should consider the continued appropriateness of the learning outcomes, measures, and targets, planning for improvements where needed.

- A review should include conversations about how assessments were implemented, and if that implementation still makes sense, assuming it did in the first place.

- Individual faculty should consider the results of their students and consider those results compared to students taught by colleagues.